Bessie Stephenson was born on January 4, 1885 in Uckfield. Her parents Tom and Eliza (neé Hobden) were living in that town, having

moved there from Iford, 3.5 miles away.

In 1891 the family - wrongly

recorded as 'Stephson' - were living at 79, Court House Cottages in Uckfield.

Tom was a gardener and Eliza was looking after the children: William (10),

Blanche (8), Bessie (6) and even Alice (3) were at school. Emily, the latest

addition, was 10 months old.

In 1901 Bessie was a housemaid at Uppark House the large

establishment of Lieutenant-Colonel (retired) Keith Turnour-Fetherstonhaugh and

his wife Caroline in Harting ,

Sussex

http://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/138290.2

For more on Uppark see

https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1000347

Like her mother, Bessie was a domestic servant; although

she'd stayed in Sussex ,

she'd moved almost 60 miles from home:

The 1911 Census shows that she was still a servant but in a

different county.

41 miles by road

She was a housemaid at Durwood, Thibet (sic) Road, Sandhurst, Berkshire. Durwood was the home of Lesley James

Probyn Butler, a 34 year old Captain in the Irish Guards and his wife Mary

Christal (aged 28). The couple had a son and daughter and only four servants in

all, so this was a much smaller establishment than Upppark.

We know from a postcard sent by her sister Alice that her

address was Durwood in October 1910 - but Alice wasn't sure if she was actually

there which might or might not mean that she was about to start there.

Captain Butler was to win the DSO in 1916. Mary Christal

Butler was the daughter of Sir John Heathcot-Amory,[1]

former M P. for Tiverton for Devon . I think it was through her that Bessie met her husband.

View of Tiverton across the River Exe: By en:User:Lew747 - en.wiki, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4603942

Herbert Eveleigh Arnold was born close to Bideford in North Devon, and in 1911 was a chauffeur for the Heathcot Amory family and living in Tiverton. Somehow the two employees came together.

They were married in the Westhampnett Registration District in the third quarter of 1912. Bessie's father, Tom, had his death registered in this district in 1907 and her mother Eliza was visiting a friend in Selsey, which is part of the district, in 1911. Banns were called on September 8 in Withleigh, Devon, where the groom was living, with Bessie's address given as Selsey. The wedding probably took place at St. Peter's Parish Church:

They were married in the Westhampnett Registration District in the third quarter of 1912. Bessie's father, Tom, had his death registered in this district in 1907 and her mother Eliza was visiting a friend in Selsey, which is part of the district, in 1911. Banns were called on September 8 in Withleigh, Devon, where the groom was living, with Bessie's address given as Selsey. The wedding probably took place at St. Peter's Parish Church:

The Voice of Hassocks: This file is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

The couple had a son, Harry E. Arnold, who was born on August 19, 1914, just before the European war broke out. The birth is recorded in the Wokingham District. Edgar Williams, the husband of Bessie's sister Blanche, was from Twyford in this District, so it's probable that Blanche and Edgar were living there and helped look after Bessie, who was giving birth while her husband was away fighting.

Mr. Arnold first joined the Royal Army Service Corps (No. 2/191842) and then transferred to the Tank Corps (75044). He was killed in action on April 23, 1917. Second-Lieutenant T. O. Norman wrote to Bessie saying that Herbert had done good work with the Corps on April 9 and 23 but was killed instantaneously by a direct hit on the latter day:

By the death of your husband, who was loved by everyone who knew him, I have lost the best man in my crew. I had previously recommended him for decoration for his excellent work. (North Devon Journal, May 17, 1917, p. 6).

Bessie was now living at Chevithorne a village close to Tiverton. This is the inscription on the Chevithorne War Memorial:

Harry never saw his father.

Wilfred Edgar tells us that Bessie became the postmistress of Tiverton; this is possible, but it's also possible that she was postmistress of Chevithorne.

In the second quarter of 1923 Bessie re-married at Tiverton. Her second husband was Josiah Richards of that town.

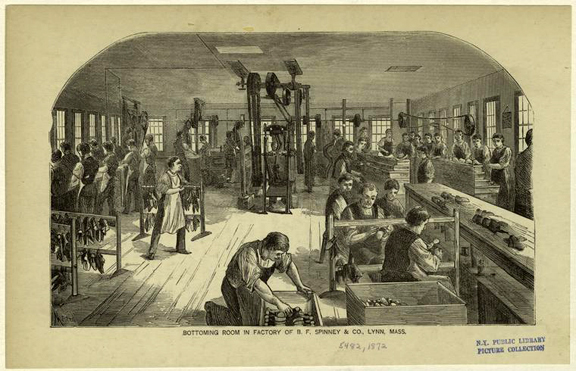

Josiah was much older than her, having been born in 1865 or 1866 in Penryn (Cornwall). He appears on the electoral register as early as 1893, so he must have moved to Tiverton by that year. In 1901 he was living there with his wife Edith (five years older than him) and five children. He was a butler. In 1911 the couple, with two children still at home and a sister-in-law moved in, were living in Samford Peverell, just outside Tiverton.

Wikipedia: By Martin Bodman, <a href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0" title="Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0

They'd been there since 1908 at the latest as he appears on the electoral register in that year. Josiah was now (1911) an agent for Prudential Assurance. In 1912 they were living at Bridge Cottage in the same town, and Josiah owned the property and some land freehold. The Cornwall Records Office holds a 'Deed of Partition and Release' signed in June 1912 by Edith, her sister Priscilla Phillips, and others, waiving rights to certain properties in St. Austell. Edith's husband is described as an 'insurance agent'.

There's a 'J. Richards', born in 1866, who was admitted into the Barnstaple branch of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters, Cabinetmakers & Joiners in 1918 and was still a member in 1921. If this is the same man, he had changed careers again.

Women (over 28) were given the vote in 1918, so on the 1918 register Josiah and Edith appear together at 2, Brickfield Terrace. In 1920 they've been joined as voters by his sons Joseph and Harold and his sister-in-law Priscilla Phillips is also registered. However, Edith is not on the 1921 register, which gives us an approximate date for her death.

So that 1923 marriage was between two people who had already lost their first spouse.

In 1924 Bessie and Josiah were on the electoral register at 2, Brickfield Terrace and the couple were still there in 1927. But by 1928 they'd moved to 209 Chapel Street in Tiverton, remaining there until 1930. By 1931 they had moved to 20, Frances Road, Windsor, perhaps to be close to Bessie's sister Alice, who had moved there in 1916/17. Although Harry was not yet old enough to appear on the electoral register, he almost certainly accompanied his mother and step-father. He was to lose his second father too.

Josiah died aged 73 in the second quarter of 1938.

In 1939 Bessie and Harry were still living at 20, Frances Road, with two other people whose records are currently closed. Harry was single and working as a paper buyer.

Mr. Arnold first joined the Royal Army Service Corps (No. 2/191842) and then transferred to the Tank Corps (75044). He was killed in action on April 23, 1917. Second-Lieutenant T. O. Norman wrote to Bessie saying that Herbert had done good work with the Corps on April 9 and 23 but was killed instantaneously by a direct hit on the latter day:

By the death of your husband, who was loved by everyone who knew him, I have lost the best man in my crew. I had previously recommended him for decoration for his excellent work. (North Devon Journal, May 17, 1917, p. 6).

Bessie was now living at Chevithorne a village close to Tiverton. This is the inscription on the Chevithorne War Memorial:

H. ARNOLD

|

75044 Private Herbert Everleigh Arnold of "C" Battery, the Machine Gun Corps (Heavy Branch). Son of Thomas and Mary Jane Arnold of the Bell Inn, Parkham; husband of Bessie Arnold of Chevithorne. Born in Parkham in 1878. Died 23 April 1917 aged 33.

|

Harry never saw his father.

Wilfred Edgar tells us that Bessie became the postmistress of Tiverton; this is possible, but it's also possible that she was postmistress of Chevithorne.

In the second quarter of 1923 Bessie re-married at Tiverton. Her second husband was Josiah Richards of that town.

Josiah was much older than her, having been born in 1865 or 1866 in Penryn (Cornwall). He appears on the electoral register as early as 1893, so he must have moved to Tiverton by that year. In 1901 he was living there with his wife Edith (five years older than him) and five children. He was a butler. In 1911 the couple, with two children still at home and a sister-in-law moved in, were living in Samford Peverell, just outside Tiverton.

Wikipedia: By Martin Bodman, <a href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0" title="Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0

They'd been there since 1908 at the latest as he appears on the electoral register in that year. Josiah was now (1911) an agent for Prudential Assurance. In 1912 they were living at Bridge Cottage in the same town, and Josiah owned the property and some land freehold. The Cornwall Records Office holds a 'Deed of Partition and Release' signed in June 1912 by Edith, her sister Priscilla Phillips, and others, waiving rights to certain properties in St. Austell. Edith's husband is described as an 'insurance agent'.

There's a 'J. Richards', born in 1866, who was admitted into the Barnstaple branch of the Amalgamated Society of Carpenters, Cabinetmakers & Joiners in 1918 and was still a member in 1921. If this is the same man, he had changed careers again.

Women (over 28) were given the vote in 1918, so on the 1918 register Josiah and Edith appear together at 2, Brickfield Terrace. In 1920 they've been joined as voters by his sons Joseph and Harold and his sister-in-law Priscilla Phillips is also registered. However, Edith is not on the 1921 register, which gives us an approximate date for her death.

So that 1923 marriage was between two people who had already lost their first spouse.

In 1924 Bessie and Josiah were on the electoral register at 2, Brickfield Terrace and the couple were still there in 1927. But by 1928 they'd moved to 209 Chapel Street in Tiverton, remaining there until 1930. By 1931 they had moved to 20, Frances Road, Windsor, perhaps to be close to Bessie's sister Alice, who had moved there in 1916/17. Although Harry was not yet old enough to appear on the electoral register, he almost certainly accompanied his mother and step-father. He was to lose his second father too.

Josiah died aged 73 in the second quarter of 1938.

In 1939 Bessie and Harry were still living at 20, Frances Road, with two other people whose records are currently closed. Harry was single and working as a paper buyer.

Judging from a family photo, Harry served in the war. On March 25, 1946 he married Aileen P. M. Yates ('Pat') in Kensington.

Pat Yates was born on November 17, 1915.

On October 21, 1921 young Pat and her family set sail for Demerara in British Guiana Her father is described on the ship's manifest as a missionary, so that was presumably why they were going. It looks like she might even have born there, as her father was appointed to work with Indian immigrants in British Guiana in 1912 (missionaryhistory-whathappenedwhen.htm).

In 1939 Pat was single and living with her father, a Methodist minister, and other family members in Rayleigh, Essex. She was working as a charity secretary. 'Yates' has been crossed out and replaced with 'Arnold', which suggests that changes to the 1939 Register were made as late as 1946. Between 1929 and 1933 the Reverend Yates had been working in the Windsor, Maidenhead and Slough area, so perhaps that was when they met.

Harry's life ended in the Islington district of London in 1965.

Bessie died in 1962 on a visit to her family.

Note: Pat Arnold remarried. In 1973 Aileen P. M. Arnold is recorded as marrying George J. T. Gilks in the St Pancras Registration District. This new name has been added to the 1939 Register!

George James T. Gilks, who was born in 1907, died in Barnet in 1992.

Aileen P. Gilks is on the electoral register between 2002 and 2006, residing at a care home in north London. She'd been there 6 years but it's not clear if that was in 2002 or 2006.

Note: This is a portrait of Pat's father from along article about him in The United Methodist, February 11, 1926, p. 64:

He is the Rev. H. M. Yates, a Wesleyan

minister who has laboured as a missionary since 1912 in

the difficult field of British Guiana. He is at present

resting in a cottage, near Land's End in the hope of

restoring his shattered health. Originally he hailed

from Wakefield, and With all his kindness and gracious

bearing could soon disclose his solid Yorkshire grit, if

you scratched him !

Mr. Yates is a very kindly personality, good to know, and he has already won the hearts of all my church members in this little village chapel of Drift.

And there's this intriguing question to the author of a blog post on British Guiana:

For his dedication and work, Peter Ruhomon was honoured by becoming the first holder of the Yates Gold Medal awarded by J. A. Veerasammy to perpetuate the name of Rev. H. M. Yates, founder of the EIYMS.

He was also a founder/ member of the British Guiana Literary Society launched by Cameron in 1930 which included Rev. Dingwall and Rev. Pollard.

EIYMS = (Wesleyan) East Indian Young Men's Society which Yates founded in 1919 in Georgetown.