Alice Edgar's great-grandfather was William Stephenson, a

shoemaker of Askham Bryan, now a suburb of York but then a village about 6 miles to the

south-west. He was born in 1781 and he married

Mary, who was born in 1791. I don't know Mary's maiden name. William was born

at Thorp Arch, about 7 miles from Askham Bryan and Mary at Long Marston, less than 5 miles away

from the village they would make their home in. Their first child (surviving

one at any rate) was also named William. He was born in 1821, followed his

father into shoe making, and married a woman called Jane - this time I think I

can take a reasonable guess as to her maiden name. Their boy Tom, born in 1857,

was Alice 's

father.

Let's see if we can put some flesh on these bare bones of

our family history.

This is from nineteenth century descriptions of Thorp Arch,

which is the currently known origin point for 'our' branch of the Stephensons:

The river Wharf

The 'arches of the bridge' have nothing to do with the

village name, which alludes to the De Arcubus (or De Arches) family, which came

to Britain

with William the Conqueror.[2]

As for Long Marston, the childhood home of first female

ancestor in this line: one of the crucial engagements of the English Civil War,

the Battle of Marston Moor, took place

just outside the village in July 1644:

At some point the couple moved to Askham Bryan (now known mainly for its Agricultural College) where they

remained for the rest of their lives.

7.8 Miles

4.9 Miles

Their son, also a William Stephenson and

my great-great-grandfather was born there in 1821. To avoid any confusion I'll

call the two Williams 'Sr.' and 'Jr' from now on but please remember this was NOT

how they were named. And while the distinction between 'Stephenson' and

'Stevenson' is said to have been important to my grandmother Alice it was of no

significance to the Census takers who used both forms - and on two occasions

recorded them as 'Stephsons' perhaps suggesting an idiosyncratic family

pronunciation!

What of the trade of shoemaker that was followed by both

William Stephenson's?

Shoe maker and apprentice, illustration of 1821

Shoemakers had been at work in Askham Bryan since the seventeenth

century.[3] William

Stephenson Sr's prospects as he set out on this path were bright: he was a

skilled worker and it must have seemed there would always be a demand for his

products. He would have served an apprenticeship - probably for seven years and starting at the age of seven - although I

don't know if, like William Jr., his father was also his 'master'. The earliest

reference to his work is in a Directory for 1823 where William is listed as a

shoemaker - and he has one fellow craftsman in Askham Bryan, John Beck.[4] It

seems certain that the two didn't live by making and repairing shoes for their

fellow villagers: they did that, no doubt, but it's likely they made most of

their money by producing shoes that were sold in York . Shoe making, like most other industries

in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, was organised in what is now

sometimes called 'the domestic system':

shoes were made at the worker's home, paid for on a 'piece work' basis by a merchant

capitalist, and taken to be sold, often from warehouses, in the nearest suitable

town[5] -

in this case almost certainly York. Sometimes the capitalist owned the tools

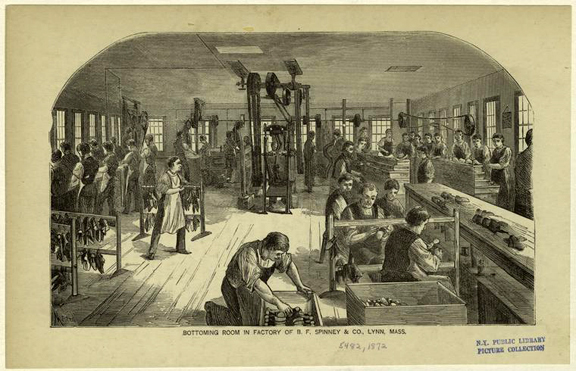

necessary for the job, sometimes the worker. As the nineteenth century wore on,

shoe making - again like other manufactures - was transferred to factories where

workers needed little skill to operate the steam-powered machinery owned by

their boss, but could produce a satisfactory much more quickly and for much

less cost than trained craftspeople like the Stephensons. In most cases,

artisans (as they were generally called at the time) were clear losers, but here

is a huge debate as to the effects of this 'industrial revolution' on the

working class as a whole. I think it would be a reasonable summary to say that

the majority - or at least a good number - of the class enjoyed slightly higher wages but the conditions of

both their work and their lives became worse in more ways than they improved.

It's hard to believe that either William Stephenson would been tempted by

higher wages to give up their pleasant rural surroundings for the streets of

nearby York, where the grim conditions faced by many workers were highlighted

by social investigator Seebohm Rowntree in an influential 1900 report.

But even those who like the Stephensons stayed out of the

rapidly expanding northern cities were deeply effected by the great changes

going on around them.

They did their work

at home, but the first factory (or factory-like) institutions for shoe manufacture

appeared in the late 1850s. In 1861,

when William Sr. died, the situation wasn't too serious because the only

process that had been mechanized was closing the uppers, which had

traditionally been 'women's work'. Nevertheless, the march of industrialisation

was unstoppable: by 1865 a single factory in Northampton was producing 100,000 shoes a

week using steam-powered machinery[6]

and in the next 25 years every process in shoe manufacture was mechanised,[7] and

skilled craftsmen like the Stephensons were driven out by mass production.

It's time to say more about the place the family lived and

worked in and its relationship to the industrial revolution. My guess is that Wikipedia's description of the village today gives us a pretty good idea of what our ancestors would have seen:

Askham Bryan was a small village. Even in the 1870s there

were only 362 people living in 68 houses.[8] In

1831 the population was 377 - the largest figure until the 1950s,[9] so

the community was not undergoing the growth experienced by northern places on

or close to the coalfields - it was coal that was powering the industrial

revolution. In the same year (1831) there

were 18 men in the category 'retail and handicrafts', which probably included

William Sr., and 44 agricultural labourers. The third biggest category was

'farmers employing labour' - 10 men. There were only 7 non-agricultural

workers. In other words, this tiny

community was overwhelmingly agricultural, but with a number of skilled workers

like William Sr. who practised their craft at home.[10]

The number of men in the category 'manufacturing' workers was zero,[11] which

means there were no factories in or near the village - about fifty years into

the industrial revolution these great changes have had no direct impact on

Askham Bryan. As the century wore on this changed a little, but not by enough

to destroy the quality of life. In 1881, when a more complex system of

classifying workers was in operation and statistics for women were also

collected, agricultural workers still easily outnumber all other categories of

male workers, while over 80% of women with known occupations were in domestic

service. There are now 4 workers in various minerals, but Askham Bryan is still

a basically agricultural community where the men work on the land and women

either don't work or go into domestic service.

This made Askham Bryan a relatively pleasant and unpolluted

place to live. And the family's position in the village wasn't bad either.

A modern analysis of social structure in 1831 places the

largest number of men in the 'labourers and servants' class (58), with 17 in

the 'middling sorts' (this would have included our ancestors), 14 'employers

and professions' and 3 'others'). So at this time the Stephenson family

occupies a solid position in the village, a cut above the average.

What of the trade followed by the two William Stephensons?

At the time of the 1841 Census, shoemakers were the largest

group of artisans (excluding the textile trades) in the country - 133,000 adult

males.[12]

They had a rather contradictory image: on the one hand, they were believed to

be the group most prone to celebrating 'Saint Monday' - taking Monday off

because they were too drunk or hung-over to work after the weekend's indulgences.

On the other, they seem to have been thought of as more literate and thoughtful

than comparable artisan groups. I think there was some truth in both stereotypes

- and I shall present evidence that places one or both Stephensons in the

second category! But if they did want to drink that wasn't a problem: in 1865 the vicar noted as one of

the impediments to the success of his religious work the presence of three pubs

in a community of not much more than 300 people.[13]

This is a good time to point out that we mustn't idealise

the life of our two ancestors. They would have worked long and hard and without

our modern 'safety net' to look after them in times of economic downturn or

personal sickness. Not being able to work meant not being able to earn, and, as

we shall see, every worker had good reason to dread old age.

With this general picture of relevant developments in mind,

we can look more closely at the particular lives of our two ancestors.

As I mentioned in my first paragraph, William Sr. and Mary gave

birth to their first child, my great-great-grandfather William Jr., in 1821.

They had a daughter, Hannah, in about 1824 - she's 27 years old in the 1851

Census. Their second son Robert was born in about 1829 - he's 12 in the 1841

Census. William Penty was born in 1840 - he's just 1 in 1841.

In that 1841 Census William Stephenson Sr. is a shoemaker living

in Askham Bryan - there is no village numbering system, - as we've seen there

were many houses - and he's on the first sheet of the records. Much of Askham Bryan is now conserved because of its historic interest, and the account of the nineteenth century village in the conservation area description suggests that their house was part of a 'cluster' of buildings around the Hall (see below). There would be a gap and then another cluster, and so on.

He is 60 and his

wife Mary is 50. Robert and William Penty are living at home, but William Jr.

isn't. Nor is Hannah, who's 17 - my guess is that she's in domestic service,

which, as we've seen, was the fate of most women of the village later in the

century when female employment starts to be recorded. To jump ahead a bit: wherever

she was, Hannah had a daughter Jane Ann in 1845[14] -

she's given as five years old and a 'scholar' in 1851. But Hannah was

unmarried, so she had returned with Jane Ann to live with her parents. Jane Ann

was born in Askham Bryan and her father is unknown.

What of Hannah's older brother, our direct ancestor? In 1841

William Jr. is following in his father's footsteps - he too is a shoemaker,

having almost certainly acted as his father's apprentice. But at aged 20 he's

moved away from home - although not very far. He is in a different house in

Askham Bryan, lodging with William Vincent (aged 50), a tailor and his wife

Hannah (60).

At some time, most probably in the early 1840s, William Jr.

married a Jane, who was also born in Askham Bryan about three years after her

husband - that means in about 1824. There's a Jane Farley, a farmer's daughter,

living close to William in 1841 - she's given as 15, but ages in the 1841

Census were meant to be rounded to the nearest five, so that means she could be

17. She disappears from the record after 1841 and no other Janes born in Askham

Bryan at anywhere near the right time come up in my searches, so she looks a

promising candidate for my maternal great-great-grandmother!

In any case, William and Jane soon began to produce the

large family characteristic of the Victorian period, when contraceptive methods

were primitive and many children died in infancy. In the 1851 Census the

couple's eldest daughter, Mary, is 9, Ann is 6, George 4 and Charles 2. Their

youngest child, Robert. was a baby - just 1 month old. Only Ann was described

as a 'scholar' - perhaps poor Mary was already working. The family still live

at Askham Bryan.

In the same year (1851) William Sr. is recorded as 70 and

his wife Mary is 60. As we've seen, their unmarried daughter Hannah has

returned home bringing with her their granddaughter Jane Ann. The family are in

the closest house to 'The Hall', where dwells Ann Fawcett a 'gentlewoman' with four

live-in servants. Nearby live a tailor, some

agricultural labourers, and a man whose both stockbroker and farmer of 71 acres

- I'd like to know more about the social relations in this very mixed 'cluster' of houses! Ann Fawcett died unmarried in January 1856 and her estate went

into the notoriously slow Court of Chancery to be squabbled over - it was still

there in 1860[15] and no

doubt this gave the village several years of enjoyable gossip.

Mary Stephenson - William Sr's wife not William Jr's

daughter - died later in 1851 - some time after Census Day which was March 30.

She's buried in St. Nicholas Church.[16]

Her grand-daughter, Jane Ann, died in 1867 and is named on her grandmother's

tombstone so is perhaps buried in Mary's grave.[17]

By Ken Crosby, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3052230

That 1851 Census also gathered information about religious

worship, so we get another piece of information about our ancestor - although

it's unfortunately not certain which one! In 1851 there were two churches in

Askham Bryan, the Anglican St. Nicholas ('an Ancient Church recently repaired'

where Mary was soon to be buried) which could cater for a congregation of about

150, and the Missionary Chapel, a Wesleyan Methodist church erected in 1836

which could seat 100. The church 'steward' who provided the information about

the Chapel to the Census takers was none other than 'Wm. Stevenson'. Nearby

Askham Richard also had a Wesleyan Chapel, which suggests that Methodism was

strong in this area. The chapel in Askham Bryan was a 'plain brick building'[18] and it was replaced in 1893 by a new chapel that has now been modified into the village hall.

Which one of our ancestors was the steward? My guess would

be William Stephenson Sr. as I think it more likely to be the 70 year old than

the thirty year old in a position of responsibility. In any case, this proves

one (at least!) of them was both literate and respected in the community - and

perhaps a man of sober and industrious habits, too, although not all Methodists

lived up this ideal of course!

But if the family was Methodist - the chances are that both

the Williams were of that faith, whichever one was the steward - is it strange

that they were buried in St. Nicholas, the Anglican church?

In 1865 William Whaley, the Anglican vicar, reported that

only 10 or 12 people in the village were absolute dissenters who had no truck

with the established church - the rest either attended both services or had no

objection in principle to so doing.[19]

Tom Stephenson - William Jr's son - had a fine voice and he's reported as

singing in either York Minster or Durham Cathedral and other Anglican churches,

so he either defected to the Church of England or was one of those willing to

combine Methodist and Anglican worship. My grandmother - Tom's daughter Alice -

sent her children to Anglican Sunday School, so by that time all trace of

'Dissent' had vanished from our line of the family.

In fact, John Wesley, although he set out to reform the

Church of England, never left it. The first Methodists - originally a term of

contempt used by their enemies - challenged a church they saw as corrupt,

spiritually moribund, and indifferent to the fate of the vast majority of the

population - the workers and the poor. According to historian Jeremy Black,

Methodism was of particular appeal to artisans (skilled workers like our

ancestors). It was often a way for them to show the proud independence from the

established order of men who possessed a valuable and hard-won skill.

What all this means is that it's likely our family were

never particularly hostile to the Church of England, and like other Methodists

were buried in Anglican graveyards when there was no one of their own

available.

William Sr. was 70 when his wife died and he faced an

uncertain future as ageing made physical work more and more problematic. There

was no old age pension, of course, and in many areas the only way for the

elderly to get any help at all was to go

into the dreaded workhouse. Although Askham Bryan did have a couple of 'grace

and favour' homes[20] where

the 'deserving poor' could live for a nominal rent, most people who couldn't

support themselves ended up in a workhouse in nearby Tadcaster. But it looks

like William Jr. saved his father from this fate by taking him into his own household,

as the 1861 Census records that there's a 'late shoemaker' and 'widower', also

a William Stephenson, aged 80, lodging with his family.

That 1861 Census shows the house must have been pretty

crowded: also living with William Jr. and Jane are Anne (16, a labourer),

George (14, a labourer), Charles (12), Robert (10), and William (7- William Jr. Jr.!). Charles,

Robert and William are at school. But

it's one of the two new additions to the family I'm most interested in: my

great grandfather Tom Stephenson is 3, and he has a baby sister Eliza aged 1.

William Stephenson Sr. died in the summer of 1861 and is

buried in St. Nicholas churchyard in Askham

Bryan. He too is on the memorial with

Mary and Jane Ann.

So far we have a picture of a family living a tough life although

somewhat above the bottom of the social scale. But even though he's well on

onto middle age, perhaps even old by the standards of the time, Willliam Jr.

(I'll drop the Jr. from now on as his father is dead) makes a remarkable

attempt to improve or rescue his social position and economic well-being.

The 1871 Census shows that he is now both a shoemaker and a farmer

of about 15 acres. He's obviously saved or otherwise acquired the money to buy

or rent a small farm. It's possible this was an attempt at economic betterment,

but it's also possible that he saw the writing on the wall and realised that

his craft skills were being made redundant by mass production (see above). And

his family had continued to grow: William, Tom and Eliza have now been joined by

Anna M. (9), Emily (6) and Arthur (4). Both Anna and Emily are 'scholars' and it's time to say something about the local

school.

It was a 'National

School British School

The school is attended

by 45 children. It is a neat brick building, erected some years ago, and is

supported by a voluntary rate and school fees. [21]

The school records in the National Archives start in 1864[22]

but another source provides an indication that there was a school in the

village in the 1820s[23]

and there was certainly a schoolmaster

(one William Jackson - but he was also a farmer so perhaps his job wasn't

full-time) in 1823[24]

so either the earlier records have been lost or there was a school in the village

before the National School. My guess is the former.

In 1865 there were 69 'scholars' aged above 5. The school

was supported by a £6 a year endowment and private donations but also got some

help from the Government. There was a Sunday School with 45 attendees that was

entirely funded by private gifts. The village was lucky: nearby Askham Richard

only had a 'dame' school and some children from that village came to get the

better education offered by the Church.

It seems that a number of children of both Williams died in

childhood or after a relatively short life by today's standards - William

Penty, for example, is mentioned only in the 1841 Census. On December 31, 1877 William Jr's daughter

Mary died at Far Headingley, now part of Leeds - 'the beloved wife of Richard Dalton'. She was 36.[25]

In 1880 there was a new development: William Stephenson was

appointed an Overseer of the Poor at Askham Bryan.[26] I

need to do more research on this position - and perhaps even to track down

William's accounts book! Before 1834 - when a major change to the English Poor

Law was introduced - the Overseers had a variety of tasks connected with the

administration of poor relief, but this changed in complex ways in the new

system.. In any case, the appointment -

whether voluntary or, as in some cases, against the will of the new Overseer -

shows that he had a certain standing in the community and that he had achieved

reasonable standards of both literacy and numeracy - skill with numbers was

common amongst shoe makers as they had to keep careful note of the foot size of

their bespoke customers.[27]

If William did have anything to do with the running of the

local workhouse he would have some grim reminders of the fate that could befall anyone. In the

Tadcaster Workhouse in 1881 was Robert

Hodgson, a former shoemaker of South Milford ,

perhaps a victim of the industrialisation I described earlier.[28]

There were seven residents of Askham Bryan there, including a family who had

lived close to William and, one Samuel Stephenson, a 15 year old scholar - I

don't know if he was a relation or not.

12.3 Miles

The workhouses had never been places of comfort and joy, but

after 1834 they became a lot worse. The Poor Law Amendment Act of that year

banned 'out door relief' - help given to the poor outside the doors of a workhouse - and to guarantee that no-one

entered a workhouse unless they really had to the Act also decreed that life

inside one should be less desirable than the life of anyone outside. Of course,

the life of the worst-off labourers was about as bad as it could be in terms of

food, shelter and so on, so the only way to make existence less desirable was

to persecute the inmates with petty rules (no talking at meals for example),

give them pointless work (breaking up stones that would never be used in some

cases) or - and this was the most hated thing of all - house the sexes in

separate accommodation so that husband and wives and parents and opposite sex

children were split up.

In practice it was impossible to implement this brutal act

in full - the attempt to end all outdoor relief was soon abandoned, for example

- but enough of it remained in place to make fear of ending up in the workhouse

a shadow over every working class life. I only know of one family member who

ended up there - a tragic story I'll

tell in a future post.

In the 1881 Census -

taken a year after his appointment as Overseer - William was described as a farmer of 16 acres - so he had held on to

his improved social and economic position in the decade between censuses. He

and Jane were living in Askham Bryan with

three children - not including my great grandfather Tom - he'd married Eliza

Hobden and had gone down to her home county, Sussex, in search of work. At home

were Robert, his age given as 29 but probably a little older, and unmarried,

who was an agricultural labourer, Arthur, 14, a 'scholar', and a granddaughter,

Florence, aged 9 who was also at school.

Perhaps she was Robert's daughter, but the Censuses only state the relationship

to the head of the household so we can't be sure.

On November 16, 1884 Eliza, described in the newspaper

report as their eldest daughter - which means that Anne must have died as well

as Mary - married Joseph Anderson of York at New Street

(Methodist) Chapel.[29] Eliza

outlived her husband, and the 1911 Census finds her working as an office

cleaner in York .

There was to be one more development in William's working

life. Bulmer's directory for 1890 tells us:

Post Office at

William Stephenson's, shoemaker. Letters via York

I guess this means his farming enterprise had failed and

he'd sought another way to supplement his income from shoe making at a time

when, as we have seen, the process had become fully mechanised and craft

production was on the way out.

The next year's Census (1891) gives us William Stephenson (69)

and Jane (67) living in Village

Street , Askham Bryan. He's described as a

shoemaker and 'postman' - it would be interesting to know how much of the

former he was actually doing. Arthur aged 34 is still living with them - he's a

groom and domestic servant. Florence ,

their granddaughter, is aged 19.

William's final appearance in the records is in the 1901 Census,

when, aged 77, he is a 'sub-postmaster' and a worker at home - so presumably

still making shoes. Jane is 74 and they are living at the post office in Village Street . I

can find no death record for William Stephenson, but one source states he died

in the early part of the 1900s. This is plausible as I can find no entry for

him or Jane in the 1911 Census either.

In 1901 Tom, living in Sussex with his 13 year old

daughter Alice probably just out of school and about to enter domestic service, was pursuing his career as a gardener. Whatever the Stephensons did now, it wouldn't be making shoes.

[1] http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Thorparch/

[2] http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/place/14363

[3] file:///C:/Users/brian/Downloads/ca14askhambryan.pdf

[4] http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Askhambryan/Askhambryan23Dry.html

[5] http://staffscc.net/shoes1/?p=126

[6] http://www.tredders.com/history

[7] http://staffscc.net/shoes1/?p=126

[8] http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/place/11226

[9] http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10389707/cube/TOT_POP

[10] http

http://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10389707/cube/OCC_PAR1831_SIMP://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/unit/10389707/cube/OCC_PAR1831

[12]https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=_IONAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA122&lpg=PA122&dq=apprenticeship+in+england+lane+shoemakers&source=bl&ots=vmcIqQgSfq&sig=MIl__bo6HwrHYLmF_k5fqBxyjYE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjRleDS_KnOAhWFAsAKHWcJCEIQ6AEILDAC#v=onepage&q=apprenticeship%20in%20england%20lane%20shoemakers&f=false

[13] https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=iBB34569X4sC&pg=PA21&lpg=PA21&dq=askham+bryan+methodists+whalley&source=bl&ots=6WBrF-piez&sig=QYZOSDwxnYm_d3tU_hL9-s2X5Q4&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiW2MHyvMjOAhWJIMAKHfqEBE8Q6AEIMTAD#v=onepage&q=askham%20bryan%20methodists%20whalley&f=false

[14] http://www.gravestonephotos.com/public/gravedetails.php?grave=57827&scrwidth=1258

[15] Perry's

Bankrupt Gazette , Saturday, January 21, 1860, Issue 1659, p.49/50.

From British Library Newspapers

[16] http://www.gravestonephotos.com/public/gravedetails.php?grave=57827&scrwidth=1258

[17] http://www.gravestonephotos.com/public/cemeterynamelist.php?cemetery=500&limit=201&scrwidth=1258)

[18] http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Askhambryan/Askhambryan90.html

[19] https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=iBB34569X4sC&pg=PA21&lpg=PA21&dq=askham+bryan+methodism+1865&source=bl&ots=6WBrE1offF&sig=KWDad9iDAP-DBtDs6xTSR_S1raA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiN6KGLjsbOAhVkI8AKHaQBCg4Q6AEIPTAF#v=onepage&q=askham%20bryan%20methodism%201865&f=false

[20] http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Askhambryan/Askhambryan90.html

[21] http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Askhambryan/Askhambryan90.html

[22] http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Askhambryan/Askhambryan90.html

[23] http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Askhambryan/

[24] http://dp.genuki.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Askhambryan/Askhambryan23Dry

[25] Deaths,

York Herald,

January 7, 1878, p. 4

[26] APPOINTMENT OF OVERSEERS, York Herald, April 3, 1880, p. 6

[27] http://www.tredders.com/history

[28] http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Tadcaster/Tadcaster1881.shtml

[29] Births,

Deaths, Marriages and Obituaries, York

Herald, November 22, 1884, p. 4

[30] http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/eng/YKS/ARY/Askhambryan/Askhambryan90Dry.html

No comments:

Post a Comment