Alice Edgar's maternal grandparents were John Hobden, who

was born in 1821 in Lindfield, Sussex and died in Hove in 1899, and Eliza Page, who

was born in 1824 in Brighton and died in Lewes in 1886.

John lived at a time of great change - even in Sussex which was a long way from the coalfields

that fuelled the growth of the

economic 'powerhouses' in Lancashire,

Yorkshire, lowland Scotland

and parts of the Midlands . He was known in his family as a great walker and two

treks he undertook during this period show how the new developments were

affecting even the largely rural south of England .

Nineteenth century threshing machine: By Unknown (Dictionnaire d'arts industriels) - cropped image from 1881 Dictionnaire d'arts industriels, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=425243

The cumulative effect of these changes is sometimes called

the modernisation of society. One

aspect of this process was a gradual shift in attitudes to violence. When he

was a young man people were hung for crimes that we would now regard as

meriting little more than a short jail sentence, perhaps not even that. In one case, at least, they were hung for actions that are now perfectly

legal and accepted, as we shall see. And public hanging was regarded as

entertainment - although educated people were already starting to turn against

the grisly spectacle, especially as children were sometimes taken 'as a

warning' - contemporary accounts suggest that the behaviour of both the young

and the old hardly suggested they were out to be reminded of the majesty of the law and the stern necessities

of justice. For many going to an execution was rather like a pleasant if rather disorderly day out. Public hangings continued in England until 1868.

The reason I'm recounting all this is that John's great-grandson tell us he walked from Lewes to Horsham - 45

miles there and back again- to see the

last man publicly hanged for sheep stealing in Sussex .

Unfortunately this is not as clear as it seems. The last case of execution for

sheep stealing in Sussex that I have been able to find took place in 1805,

sixteen years before John's birth.[1]

And it seems the last man to be publicly hanged anywhere in England for this

crime was John Clarke, who paid for what he did - dying in 'a proper and

penitent manner' after receiving the sacrament -on Friday 19 March, 1830 at

faraway Lincoln.[2]

So John walked to see a man hanged, but for what crime?

I have a theory. I think John saw what many of us would now

call the judicial murder of a young man. If my theory is correct, John himself

was possibly even younger than the victim and the nature of 'the crime' gave

him an incentive to tell his family that it was 'sheep stealing' even though it

wasn't.

First of all though, the tragic hanging took place in the County Goal-

I believe that John witnessed one of these executions: the

hanging of John Sparshott for sodomy - or, as another source puts it, 'an

unnatural crime'.

The first name of the unfortunate victim is given as

James as well as John[4]

and his surname also takes the form 'Sparsholt'.But the date of the event is clear. This is from the Brighton

Gazette, a local newspaper:[5]

The return {the

Government had asked for a report of those executed at Horsham in the recent

period} contained the names of Richard

Shepherd for burglary, and James Sparshott for an unnatural crime, convicted at

the last Summer Assizes, and executed at Horsham on the 22d August last.

That makes the

execution August 22, 1835. A local historian claims it was the last public hanging at Horsham[7] -

which would make the story that John saw the last public hanging more credible,

even if he declined to tell his family the true nature of the crime. Against my theory is the fact that Richard Shepherd was hanged for burglary on the same day and surely the family tradition that preserved the memory of John's walk would have also recorded the fact that he saw two men hanged. I have a hunch, though, that this was the execution John saw and the 15 year old was too embarrassed to report the nature of crime so substituted the more innocuous one of sheep stealing.

The next thing we hear of John is in the 1841 Census when he

was an agricultural labourer living in one of the cottages at St. John Under

the Castle, Lewes. If I'm right in identifying his 'execution walk' he'd been in Lewes for at least six years.

12 Miles

However, this is just

one snapshot of a working life that seems to have been a lot more varied:

As a young man he was said to have had employment at one

time as a shepherd; at another occasion as a cowman and general dogsbody to

farmers within the county, so with long personal experience, was very useful in

handling livestock - horses, cattle, sheep, poultry - and in all-round

landwork.[9]

At about the time of the 1841 Census, Eric Hobden tells us that John

walked the same rough land from Lewes to Horsham to watch the arrival of the first steam train in Sussex .

It came from London Bridge station. The creation of the London to Brighton railway was complex, but I think the most probable date for John's

walk was July 12 1841.[10]

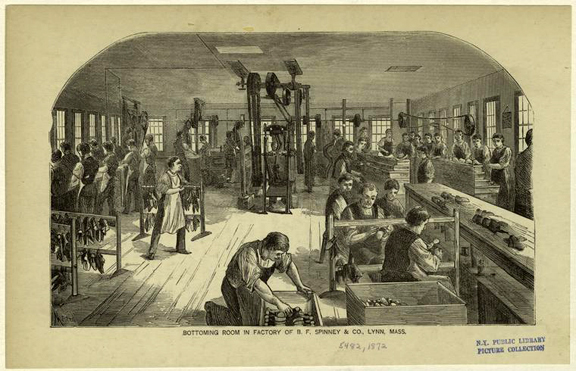

The railways were creating a new world.

English and Scottish Railways 1850: By Charles F. Cheffins - Cheffins's Map of English & Scotch Railways, 1850 (preserved at University of Chicago Digital Preservation Collection), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31265009

Industry was

stimulated to even faster growth and individuals felt their horizons expand as travel

became quicker, easier and cheaper. The train journey from London

to Brighton took less than half the time of

the coach and was much safer and more comfortable.[11]

Even standard national time came from the railways: the clocks at stations were

the first co-ordinated timepieces.

John's was right to think it was worth making the effort to

be there- it was a historic day!

John married Eliza Page at Newick on February 25, 1847.[12]

This is what Eric Hobden tells us about his great-grandmother:

Eliza (was) a

delicate, rather gentle lady who gathered her children round when they were

young in thunderstorms to sing 'O God our

help in ages past'.

The 1851 Census finds the couple still living in Newick.

8.2 Miles

John is an agricultural

labourer and Eliza isn't working - or, to put it another way, she's working

very hard looking after her husband and her house and making ends meet. On Census

Day they're being visited by 6 year old

Martha Page from Lewes - I'm not sure if she's Eliza's niece, cousin or sister.

Family tradition states that the couple lost their first

four babies at birth or soon after. The first child to survive was named after

her mother: Eliza (Jr.) was born in 1853 - she. was to become Alice Edgar's mother. Richard

followed in 1854 - and by the time of the next Census he and Eliza had three

younger brothers.

In 1861 John and Eliza are living at Church Cottage, Chailey

with Eliza (Jr.) who's at school, as are Richard and William, aged 5. Alfred is 2 and baby Robert

just 8 months. The first three children were born at Newick and the last two at

Chailey, so the family must have made the short move some time between 1856 and

1859. John is still an agricultural labourer, but maybe he's got a new job.

A word about Robert - his full name was Robert Owen Hobden

and it seems most unlikely that he was not named after the great philanthropist, socialist, reformer and creator of model factories, Robert Owen, who had died two

years earlier in 1858.

John Cranch: Robert Owen in 1845: By John Cranch - painting of John Cranch 1845, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=719799

Owen's House at the model factory in New Lanark, close to Glasgow which he managed and part-owned: By Gordon Brown, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=484332

The previously irreligious Owen converted to

Spiritualism in 1854, but I doubt that was the reason for the naming. I think

one or both of the Hobdens was probably a socialist - and perhaps this was

passed on through Eliza (Jr.) to her daughter, my grandmother Alice Edgar. Eric

Hobden notes that she was always interested in anything that improved the lot

of ordinary people and it sounds to me as if she was a left-winger long before

she got involved with the Labour Party and the Co-operative Movement in Windsor in the 1920s.

The next Census marks a shift in John's working life.

In 1871 he was a gardener, living with Eliza at 75 South Street ,

Chailey. Richard, aged 16, William (14) and Alfred (12) were all agricultural

labourers - even Robert Owen, aged only

10, was working in the fields. Only Sarah Ann (7) is at school. Lydia Fanner,

John's seventy-year-old aunt, was also

there on Census Day. All of the children are now said to have been born in Newick,

but I'm almost sure the 1861 division between the two villages is correct.

There's no sign of John and Eliza in 1881 or of John in

1891. Eliza Hobden's death aged 62 was registered in the April-June quarter of 1886 in Lewes. John's death, aged 78, was registered in the first quarter of 1899 at Steyning. The

Steyning registration district includes Hove .

I have no idea why they are not in those two Censuses - perhaps

they are and I and the other family historians who've put Trees on Ancestry.com

have simply failed to find them. But with these clues and Eric Hobden's letter

we can try to reconstruct John and Eliza's movements in the last period of

their lives.

This is what Eric tells us about John:

(H)e lived some time

of the time with Aunt Sallie and Alfred King as well as with my Grandparents

(Robert Owen Hobden and his wife Charlotte).

On March 27, 1886 Robert Owen Hobden and Charlotte had a

son, Arthur, whose birth was registered in Lewes: this places them in Lewes,

where Eliza's death was registered just before -so I think that John and Eliza

were living with Robert and his wife at that time. In 1881 Robert was working

at a footman at a large house called Newick

Park

There is, by the way, an intriguing Edgar mystery about that

marriage: Charlotte was from Somerset ,

but the church the couple married in was St.

George's , Hanover St.

Paul 's, Knightsbridge, but Hanover Square was close to the home that

Alice worked in

as a parlour maid in 1911. There's a long gap between 1884 and 1911, but we

don't know when Alice first went to work in that

part of London and I think it's just possible

that Charlotte kept in touch with her old

employers and put in a word for Alice

when some neighbours needed a servant. It's also worth noting that in 1891 her

husband (Robert Owen) was a butler for an Australian in Reigate and Alice 's employer was an

Australian widow.

Eric tells us a little about his life with Robert Owen and Charlotte:

Seemingly he (John) did not have any formal education so was thought not able to write, and definitely could not read...(but) he liked newspapers being read aloud to him. This charming pastime was provided by Florence, a friend of...Charlotte's, but the kind old lady's own reading ability was little above kindergarten level and the outcome was sometimes riotously funny. When Florrie found difficult passages (she) simply spoke out the parts she understood, and for those which puzzled her (she) just said 'Big Word' as replacement! In other instances she invented a lot of nonsense as she went along. The old man, despite lacking 'academic' knowledge, was no simpleton, so when this good soul read aloud some piece outrageously 'haywire', he would call out, 'It doesn't really say that does it Flo; it sure sounds quite daft...'

The Robert Owen Hobdens were in Hove

by 1911 but my guess is that at the time of his death in 1899 John had moved in

with his daughter and her husband. 'Sallie', as she's called in Eric's letter, was the family name for Sarah Ann Hobden, who was born in about 1864 and married Alfred King. In 1891 they

were living in Argyle Road

in Brighton . This was in the Preston sub-district of Steyning.

John Hobden was in most ways a man rooted in the old world,

but one day in July 1841 he walked over 20 miles to watch a new one come into

being. The world he died in was very different from the one he was born into - and if he'd lived a little longer he would have encountered a century in which the pace of change was to become faster still.

[1] http://sussexhistoryforum.co.uk/index.php?topic=2284.0

[2] http://parishes.lincolnshire.gov.uk/Files/Parish/91/websitehistoryCLARK1.pdf

[3] http://sussexhistoryforum.co.uk/index.php?topic=2284.0

[4] http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/1836news.htm

[5] January

7, 1836 - cited in http://rictornorton.co.uk/eighteen/1836news.htm

[6] http://www.capitalpunishmentuk.org/1828.html

[7] http://sussexhistoryforum.co.uk/index.php?topic=2284.0

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Pratt_and_John_Smith

[9] Eric

Hobden, Letter, 1986.

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_and_Brighton_Railway

[11] http://vichist.blogspot.co.uk/2013/10/with-opening-of-london-to-brighton-rail.html

[12] http://person.ancestry.co.uk/tree/7622423/person/-584703941/facts